written by: Ran Levi

This article explores the role of WW2 technology in the Battle of the Atlantic. How did technical innovations by German, American and British engineers determine the ebbs and flows of the naval battles and the ultimate fate of the German U-Boats fleet?

This article is a transcript of a podcast. Listen to the podcast:

Part I – Battle of the Atlantic (Download MP3)

Part II – U-Boats, Wolf Packs and Floating Coffins (Download MP3)

Subscribe: iTunes | Android App | RSS link | Facebook | Twitter

Explore episodes in other categories:

Astronomy & Space | Biology & Genetics | History | Information Technology | Medicine & Physiology | Physics | Technology

Part I – Battle of The Atlantic

When Hitler decided to invade Poland in 1939 the German navy had only twenty-four warships — in accordance with the armistice agreements Germany had signed at the end of the First World War, which placed severe limitations on German military forces. Great Britain — Germany’s main enemy during the first years of the war — was an enormous empire with the world’s largest fleet — over 300 ships — and ports all over the world.

Even so, the small, outgunned German fleet managed to strike painful blows to Great Britain by aiming directly for its soft underbelly. The Germans almost succeeded in cutting off Great Britain’s shipping lanes, and thus its supply of fuel and raw materials. The credit for this success belongs to the German flotilla of submarines: the Unterseeboots, or U-Boats in English.

Great Britain and its allies — mainly the US and Canada — had to contend with the German U-Boats in a constantly changing technological environment. The battle between the Allied fleets and the German submarine navy serves as a prime example of WW2 Technology, and the important role that was played by science and technology in determining the outcome of World War II.

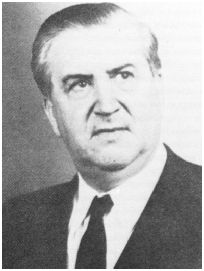

Karl Dönitz

Karl Dönitz enlisted in the Imperial Navy in 1910 and during World War I, he served as an officer on a battleship in the Black Sea. When the ship was drydocked for repairs Dönitz was stationed on land, as the commander of a small airport in the Ottoman Empire, which was allied with Germany. Dönitz, who was a highly motivated officer, was bored with his new posting and volunteered to serve in Germany’s submarine fleet. In 1918 he received his first command of a submarine, but not for long: only a month later a British battleship sunk his U-Boat and Dönitz was taken prisoner.

After the war, Dönitz returned to Germany and served in its armed forces. He quickly climbed the ranks and by 1939 he was given command of the entire flotilla of U-Boats. Like the rest of the German navy at that time, it wasn’t in great shape. In fact, the armistice agreement at the end of WWI didn’t allow Germany to have any submarines at all. Under the guise of academic research and co-operation with other nations, the German navy had continued to develop the technologies necessary for a fleet of submarines – but even so, when WWII broke out Dönitz had only 57 submarines — and less than half of them were actually sea-worthy.

Low Expectations

In addition, almost no one — either in Germany or in Great Britain — believed that submarines would ever play any significant role in marine warfare. And they believed that for two reasons.

The first was their experience during WWI. During the first half of the Great War, German submarines did manage to damage British battleships and Merchant Marine ships that were carrying essential equipment and raw materials. But, as soon as Great Britain began organizing its commercial shipping in convoys, rather than each ship traveling on its own, the submarines became far less effective. A lone merchant ship was easy prey for a submarine, but a crowded convoy escorted by armed battleships was a harder nut to crack. The Germans lost 178 U-Boats during WWI, more than half their entire fleet — without managing to significantly disrupt the British lines of supply.

The second reason was the invention of sonar — a new technology that the British developed in the interwar period. Sonar can locate a submarine by sending out a pulsed sound wave and then listening to the echoes returned by the sub’s metal shell. Sonar deprived the U-Boats of their main advantage — stealth — and that threatened to make them irrelevant.

Serious Technological Problems

But as we have already learned, when WWII broke out the German navy was far inferior to that of Britain, and so it couldn’t break through the British siege of Germany’s ports. So, Marine combat by submarine was really the only option that Germany had.

And if their numerical inferiority wasn’t enough — the U-Boats suffered from serious technological problems. During the first few months of the war, there were several occasions when German subs encountered British ships and launched surprise attacks — only to discover that none of their torpedoes worked! Some of them would pass under the hull of their target, others would hit the side of the ship but then fail to explode. It took a long and comprehensive investigation for the engineers to find the reason for these malfunctions — the fuses of the torpedoes were overly sensitive to high pressure. They finally resolved the problem, but not before a bunch of Quality Control officers were court-martialed and thrown into the brig.

So, in the first months of WWII, the German U-Boats didn’t have much effect on commercial shipping in the Atlantic. Furthermore, the number of new ships that the British put into active service each month far exceeded the number of ships that the Germans managed to sink.

The Turning Point

The turning point came in June 1940, when Germany occupied France. Until then the German U-Boats had access only to the North Sea, forcing them to make the long and dangerous trip to reach the Atlantic, where the actual naval battles were taking place. The occupation of France gave the Nazi fleet access to ports along the shores of the Bay of Biscay — a wide body of water leading directly into the Atlantic — and so that really shortened the distance the U-Boats had to travel to reach their targets. The U-Boats had enough fuel to stay underwater for longer periods of time and so Karl Dönitz – the Commander of the fleet — intended to prove to his naval comrades that his crews were going to turn the tables and do far more damage to Britain’s armed convoys than they had in WWI. The tactic that Dönitz chose to employ was called “wolf packs.”

The Germans had already tried the “wolf packs” method during WWI: several U-Boats would congregate around a convoy of commercial ships and attack all of them at once. Such an orchestrated attack would throw the convoy and its armed escort vessels into panic and confusion, as lethal torpedoes sped toward the ships from every direction. It was a great idea – but only in theory. In practice, it called for precise co-ordination between the U-Boats, to ensure they didn’t get in each other’s line of fire during combat. The U-Boat commanders were fully occupied overseeing the operation of their vessels, so it was up to the commander on shore — who saw the complete tactical picture — to “conduct the symphony” and make optimal use of all combat resources. During WWI wireless radio transmission wasn’t advanced enough to allow communication over such large distances and the “wolf pack” attacks were unsuccessful.

But by WWII, the communication technology was more developed and Karl Dönitz believed THAT would be a game changer. The U-Boats now had better, stronger radios and the antennas operating on the shores of France enabled the shore commanders to communicate with those at sea. The German fleet also had a powerful encryption device called Enigma. Enigma looked sort of like a typewriter, but inside it housed an incredibly sophisticated system of disks and gears that converted the words that were typed into a code that — at that time — was thought to be unbreakable. All that new technology enabled Dönitz to conduct his “wolf pack” tactics the way they should be done.

The U-Boats Happy Time

In less than a month after the German occupation of France, the situation in the Atlantic changed dramatically. A German sub that spotted a British convoy would transmit an encrypted message to the onshore commander, who ordered all U-Boats in that area to set up an orchestrated ambush on that shipping lane. The U-Boats attacked simultaneously, on cue from shore command, sowing death, and destruction. In some cases, the wolf packs sunk a third or even half of the ships in a convoy. The losses in naval combat are usually measured in tonnage — the total weight of the enemy ships that each side managed to sink. Before the occupation of France, Germany had managed to sink a monthly average of 80,000 tons worth of British ships; after July 1940 that number would reach upwards of 230,000 per month. The U-Boat crews called the months following the occupation of France the “Happy Time”.

The sudden German success caught Britain with its pants down. The British were totally convinced that the Germans wouldn’t dare attack with subs — not after their dismal failure during WWI — and as a result, they were woefully unprepared. In 1935, four years before the war broke out, only 11 out of over 1,000 British naval officers were trained in anti-submarine warfare.

Even Sonar — the revolutionary WW2 technology that the British were sure would win the day — turned out to be inadequate. Sonar was only effective against subs when they were underwater; when a sub was on the surface the echoes of the audio signal it returned were distorted and a U-Boat could only be detected at a very close range. Lucky for the Germans, their U-Boat hulls were well-suited to sailing on the surface, so that’s where they spent most of their time, diving only when necessary to flee their enemies. The U-Boat commanders traveled on the surface, under the cover of night, and thus managed to take the British by surprise time after time.

Nothing But Admiration

The German command was pleased with the unexpected success of its fleet of U-Boats. Hitler ordered the shipyards to immediately speed up the production of submarines. Karl Dönitz became one of the most admired officers in all the German armed forces and during the war, he rose to command the entire navy. His meteoric rise was partly thanks to his well-known anti-semitic zeal and ardent support for Hitler and the Nazi party. And he was not alone; many of the enlisted men and ranking officers had radical far-right views and had eagerly welcomed Hitler’s rise to power.

It’s not hard to understand why the German people had nothing but admiration for the U-Boat crews. They represented the values and ideals that Germans wanted to see in themselves: patriotism, unity, courage, and technological superiority. The living conditions in the crowded and claustrophobic submarines — fifty men living together in a space the size of three train cars — made it hard enough to simply maintain a daily routine, let alone face the grave dangers they faced week after week, both in combat with the British and when braving the turbulent storms of the Atlantic Ocean. In a submarine even a simple task like flushing the toilet could be potentially lethal. At least one of them sank when a sailor failed to operate the flushing mechanism correctly and sea water flooded the batteries . . .

The commanders of the U-Boats were even more admired. The Commander was the only man looking through the periscope during combat, so he bore sole responsibility for the safety of the submarine and the success of its attack. Daring and fearless commanders became well-known celebrities much like successful pilots did, and crews on leave were generously pampered with gourmet meals and dances, and women would fall at their feet.

The Canadian Navy

The British were suddenly under tremendous pressure. The wolf packs hit the supply convoys time after time, threatening to cut Great Britain off from its overseas colonies — the source of its power. The Americans had not yet declared war on Germany and not even the enormous British fleet could protect the convoys over the vast distances of the Atlantic. Desperate, the British asked Canada to help protect their convoys, at least on the western side of the ocean.

As part of the Commonwealth, Canada was one of Great Britain’s natural allies and had joined in the war effort right from the beginning. Canadian soldiers had fought in WWI and suffered heavy casualties — most of them on land. Unwilling to face a similar fate in this war and preferring to remain a free-standing Canadian force rather than be swallowed up in the British army, the Canadian government was more than happy to agree to this request.

But there was one problem, and not a minor one: Canada didn’t have a navy. To be exact, Canada had six destroyers — but they had been attached to the British fleet as soon as war broke out. In other words, every Canadian who knew the first thing about commanding a battleship was already on the other side of the ocean. The Canadian shipyards went full steam ahead in building new ships, but still, there was no one to command them.

An Unanticipated Growth

Volunteers from all walks of life enlisted in the navy. On most of the new ships, there were only four or five sailors who had any experience at sea – most of them in the Merchant Marines – along with another forty men who had never before left port. The instructors at the naval training centers were forced to accommodate the demand and even students who had failed every test were posted on combat ships. After all, better a cadet who had failed the course than one who had never even signed up for it in the first place…

In less than a year and a half, the Canadian navy grew fifty times over, from 1,800 sailors to almost 100,000. To put that into perspective, the American navy increased only twenty-fold during the entire war.

This unanticipated growth obviously took its toll on the performance of the ships at sea. One Canadian officer wrote in his memoir that:

“At the beginning of the war, most of the new ships were not at all functional. Some of them barely managed to leave port and, if they did make it out to sea, needed a lot of luck to find their way back.”

One popular anecdote tells of a senior officer who saw a ship making a particularly inept maneuver; he sent a furious message to its commander — “What the hell are you doing?” The response — “Mostly learning.”

These novice sailors were thrown into service under particularly difficult conditions. The Canadian government didn’t have the budget to built large destroyers so it approved a crash building program for a Corvette, which was essentially an improved version of a whaling boat. The small corvettes — only sixty meters long — rocked like walnut shells in the high waves of the North Atlantic and their crews suffered terribly from seasickness. The ships, which were slower than destroyers, were equipped with minimal and obsolescent armaments — and they had to do combat with the skilled and experienced crews of the U-Boats…

An Essential Role

People say a lot of things about Canada — that they could have adopted British culture, French cuisine, and American technology, but instead chose American culture, British food, and French technology. They say Canada has only three seasons — almost winter, winter, and still winter. They say the Canadian summer is the nicest day of the year. But no one can deny this one thing: they don’t give up easily.

Between 1941-1943 the Canadian Navy played a significant role in the battle for the Atlantic Ocean. The Canadians provided escorts for approximately 35% of the convoys and were active participants in over half of the naval battles. Canadian corvettes sank close to 50 U-Boats — and they did so at a high cost to themselves. However, the Canadians do not often receive credit for their part in the war. Both the British and the Americans essentially regarded them as a bunch of undisciplined amateurs. But in hindsight, we know that the Canadian navy played an essential role in the battle for the Atlantic, and they did that despite the severe disadvantage they started out with.

Captured Enigma

Nothing can take the place of courage and determination, but luck also plays its part in the war. On the 27th of April, 1941, the British got lucky and things took a turn in their favor.

That day, the U110 U-Boat attacked a convoy in the North Atlantic, east of Greenland. The attack was a success, sinking three merchant marine ships, but unfortunately for the submarine, it was spotted and pursued by two destroyers escorting the convoy. U110 was hit badly, and its commander decided that all was lost. He ordered the crew to surface the ship and abandon it.

And here’s where the British got REALLY lucky. U110 was carrying an Enigma encryption device. German navy procedures regarding the Enigma were clear: the commander must ascertain that the Enigma device has been destroyed before abandoning ship, to prevent it falling into the hands of the enemy. In the case of U110, the commander was sure that it would sink at any moment and that the Enigma would go down with it. He jumped ship with the rest of the crew, began swimming away, but a few minutes later he noticed the sub was still afloat. And that’s where it clicked: he’d made a terrible mistake. So he started swimming back towards the U-Boat. But before he could get there, he was shot and killed.

The British boarded the sub, found the Enigma, and immediately knew what they had on their hands. For a while, the capture of U110 was kept strictly confidential — even from their American allies. The Enigma was delivered to British intelligence, and Alan Turing and his group of code-breakers at the Bletchley Park facility succeeded in breaking the German code.

By intercepting transmissions from the U-Boats the British could guide their convoys between the packs of subs lying in wait for them – and if a U-Boat was detected, the convoy’s armed escort vessels would attack it with depth charges. Depth charges were the allies’ main weapon against U-Boats — but what are they and how do they cripple a submarine?

Depth Charges

A depth charge is a barrel of explosives that is dropped or thrown over the side of the ship and set to explode at a predefined depth. When the charge detonates, it creates a shock wave that can break open the submarine’s hull. But for this kind of catastrophic damage to occur, the charge would have to explode very very close the submarine: 12 feet or less, usually – and since depth charges are ‘dumb’ bombs and were fired blindly – the chances of an actual direct hit were close to none.

However, there is a secondary mode of damage, which can render even a near miss potentially destructive. At the moment of the explosion, the burning hot gasses quickly spread, creating a zone of high pressure and a shock wave. When the gasses cool off, the pressure in the detonation area drops rapidly: at some point, the pressure of the surrounding water becomes higher than the pressure inside the detonation zone. This causes the gas bubble to implode, and this implosion creates a second, less intense shock wave. Both these shock waves hit the sub in rapid succession, one after the other, causing the metal shell of the sub to alternately stretch and bend, like a spoon in the hand of a skilled magician. And much like the spoon, the accumulative stresses of stretching and bending weakens the hull. If enough depth charges are dropped near the submarine, the many smaller shock wave can ultimately cause the metal to split and rupture.

The 2nd ‘Happy Time’

The large number of battleships that the US provided to Great Britain, together with the practical experience gained by the British and Canadian crews as they contended with the submarines, brought that so -called “happy time” of U-Boat activity to an end. The number of successful German attacks plunged, and Admiral Dönitz was forced to reconsider his strategy.

In December of 1941 the United States entered the war and Dönitz recognized a golden opportunity. He sent his U-Boats to the eastern coast of the US to attack ships moving north and south, parallel to the coast. Unlike the British and Canadians, the American crews had no experience with submarine warfare and they underestimated the threat that the U-Boats presented. Only troop carriers were provided with escorts and protection; merchant ships continued to sail alone. This mistake extracted a heavy price: within seven months about 600 merchant ships were sunk in the area between North America and the Caribbean islands. This was the “second happy time” of the German U-Boats.

The Air Gap

Once the Americans began traveling in convoys to protect their merchant ships in the eastern basin of the Atlantic, Karl Dönitz redirected his attention to the middle of the ocean.

Reconnaissance aircraft posed a significant threat to the U-Boats during daylight hours, forcing them to operate only at night. But the middle of the Atlantic Ocean was an enormous area and there were no Allied patrol aircraft there since land-based planes could not fly that far. This area, known as the Air Gap, was a perfect hunting ground for the wolf packs and from the beginning of August 1942 the U-Boats mercilessly struck the convoys. Dönitz now had about 350 U-Boats in active service and up to 40 of those subs would launch a concentrated attack against a convoy. The Germans also modified their Enigma devices, so Britain could no longer decode their communications and intercept transmissions between the U-Boats and their shore command.

March of 1943 was the most successful month of the German U-Boat fleet during the entire war: Dönitz’s crews sunk 120 Allied ships, while only losing twelve German subs. Allied losses in the mid-Atlantic were so great that this was the only point at which Britain’s leaders feared they may lose the war. As Winston Churchill wrote in his memoirs:

“…the only thing that ever frightened me during the war was the U-boat peril.”

And if that wasn’t enough, Dönitz had another card up his sleeve — a new kind of submarine that would change the face of the naval combat arena. This U-Boat was said to be faster, stealthier and more dangerous than anything the allied forces had encountered.

Part II – Elektroboot

When WWII broke out, the German fleet was small and weak – especially when compared to the mighty British navy which ruled the seven seas. In particular, the German submarine fleet was a mere shadow of what it once was in the first World War.

But under the leadership of Admiral Karl Dönitz, the German U-Boats became a mighty force that terrorized British merchant ships. In July of 1940 alone, the U-Boats sunk merchant vessels with the combined weight of over 230,000 tons. The U-Boats ‘wolf pack’ attacks threatened to cut off supplies of food and fuel to the British Isles.

In 1941 the British and Canadian navies managed, with great effort, to turn the tide and curb the U-Boats threat in the North Atlantic – but Dönitz skillfully diverted the U-Boats’ deadly potential to the eastern and middle parts of the Atlantic, where the U-Boats commanders exploited the American’s navy lack of anti-submarine warfare experience, as well as the ‘Air Gap’ in patrol aircraft coverage. By 1943, Germany had about 350 U-Boats in active service, and in March of that year Dönitz’s crews sunk 120 Allied ships, while only losing twelve German subs. To make matters worse, Germany was about to introduce a new kind of U-Boat – one that would deal a deadly blow to the British, American and Canadian forces.

Prof. Helmut’s Sub

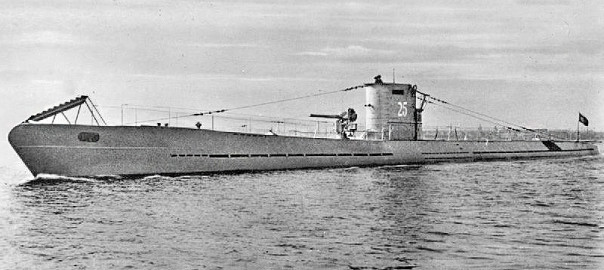

The Germans used a number of different submarine models during the war, and the main one was Type VII. It was considered the workhorse of the fleet and carried out most of the patrols and attacks. Type VII subs were considered top quality and reliable, but they had one major drawback — their speed. On the surface they traveled at 17 knots, about 20 mph, comparable to the speed of the average battleship- But underwater their maximum speed was only seven knots, meaning that if, after being spotted by an enemy ship, the U-Boat dove to make its escape below the surface, it couldn’t get away fast enough to avoid the risk of being hit by depth charges. The U-Boat’s engine was to blame for being so slow under water. The main engine was a powerful diesel but — since diesel fuel requires oxygen — it could only be used on the surface. When submerged the U-Boat was powered by an electric motor with relatively weak batteries and that slowed it down.

Before the war, Karl Dönitz had been contacted by a scientist named Helmut Walter. Walter had invented an engine that did not require oxygen. The key to this innovation was a liquid called ‘perhydrol,’ or Hydrogen Peroxide. Each molecule of Peroxide contains two atoms of hydrogen and two atoms of oxygen. A special system separated the Peroxide into water and pure oxygen and injected the oxygen into the diesel engine, thereby generating combustion. A submarine equipped with Walter’s engine could remain submerged for a very long time, with no need to surface.

In order to take full advantage of the engine’s capability, Professor Walter designed a new body for the U-Boats. The existing hulls were v-shaped, similar to those of surface ships: this gave the U-Boats improved stability on the surface – at the expense of increased friction which slowed down the submarine. Walter replaced the v-shaped hull with an elliptical, tear-shaped body that created less friction with the water. Walter’s calculations showed that the combination of a powerful engine and reduced friction would enable the sub to travel underwater at a speed of almost thirty knots! This was faster than any vessel in the Allied navies. In fact, Walter’s new design was so effective that after the war it was adopted by the Americans and successfully integrated into their nuclear submarine program.

Technical Difficulties

Karl Dönitz was greatly impressed by Walter’s invention and approved the continued development of the concept, but for the first two years of the war, this development was painfully slow. On paper, an engine powered by Peroxide was a good idea. BUT when the engineers tried to implement it they encountered many difficulties. For one, peroxide was found to accelerate corrosion in the fuel pipes. For another thing, peroxide fuel was really dangerous: if there was a sharp bend in a pipe, the increased pressure generated at that bend sometimes caused spontaneous combustion of the peroxide. This phenomenon forced the engineers to redesign the fuel system of the entire submarine.

The Germans realized that it would take years to resolve all the technical difficulties. So in December 1943 Dönitz convened his high command to determine the future of the new submarine. Their prediction for how long it would take to complete development was – not encouraging and the project seemed to be in danger of cancellation. However, two engineers who were taking part in the discussions proposed a surprising idea.

In order to increase the distance it could travel without refueling, Professor Walter’s new submarine had been equipped with an especially large fuel tank intended to hold the peroxide. The two engineers suggested removing the peroxide engine and its fuel tank, and in their place, installing two regular engines: one an air-based diesel engine and the other electric. The space that the peroxide engine had occupied would be filled with batteries for the electric engine. The significant boost provided by the batteries would greatly increase the power of the electric engine: the anticipated speed underwater would be 18 knots — certainly less than the speed provided by Professor Walter’s engine, but still more than twice than the speed of the Type VII U-Boat. And most important — the new design was based on existing engines and proven technology, so its development could be completed in a few months instead of a few years.

Karl Dönitz realized that this breakthrough could determine the outcome of the war. Such a fast submarine would be able to attack its target at very close range and then dive and speed away before the enemy ships had time to launch a counter-attack. The U-Boats’ high speed would also enable them to patrol vast areas of the ocean and locate more convoys. These new, highly innovative submarines would be able to impose a naval blockade on Great Britain! And cut off its supply of raw materials and bring its armaments industries to a standstill.

As the engineers predicted, within only six months the development process was complete. and in June 1943 Hitler approved the production of the new U-Boat– Type XXI or ‘Elektroboote’.

New Weapons For The Allies

While the new submarines were becoming a reality, the Allies again seemed to be winning the war. On October 30, 1942, a British patrol plane spotted submarine U-559 in the east basin of the Mediterranean, about 90 miles north of Egypt. A number of destroyers attacked it, causing serious damage and forcing its crew to abandon ship. Three British sailors rushed to enter it before it sank and managed to salvage an Enigma device and secret codes. Two of the British sailors went down with the sub, but their sacrifice – was not in vain. With the device and codes, the intelligence team at Bletchley Park was AGAIN able to break the Nazi communication code. And the supply convoys once again eluded the German U-Boats that lay in ambush for them.

At the same time, the Allied warships that escorted convoys were equipped with a new weapon that was more effective than depth charges: the Hedgehog anti-submarine mortar, which fired barrages of a few dozen mortars from the front of the ship. These mortars fell toward the sea bottom like lethal rain that detonated upon contact with the body of a submarine. The chances of making a direct hit on a U-Boat were small, but the enormous number of mortars made them a serious threat to the Germans.

But out of all the technological innovations adopted by the British and Americans during 1943, there were three that had a crucial effect on the course of the war. These were the ‘Huff-Duff’, Radar, and aircraft capable of long-distance flight. Each of these was revolutionary in itself — in combination? they were lethal.

The Huff-Duff

Let’s start with, the Huff-Duff. It might sound like a good name for a child’s toy, but it actually gave the submarine’s commanders a big headache.

The High-Frequency Direction Finder (HF/DF), nicknamed the Huff Duff, was used to detect the exact location of a submarine – by listening in on its radio transmissions. It was based on the fact that radio waves, like the ones submarines use to communicate with the shore, spread out in all directions, like the concentric circles of ripples when a rock falls in a lake.

Imagine standing on the shore of a lake and watching such ripples. It’s easy enough to see the general direction they are coming from, but a lot harder to determine the distance they have traveled or the exact point of origin. Were they created by a large boulder that fell far from the shore or a pebble that landed a short distance away? Radio Waves behave in much the same way. So when a submarine sent out a radio transmission, the allied receiver could detect the general direction the transmission was coming from – but not how far away the submarine actually was.

But if you have two direction finders, each in a different position, that’s a different situation. Each finder will discover the direction of the antenna — i.e., of the submarine sending out a signal — and the point where these two paths intersect provides a good estimate of the location of the sub. That was the role of the Huff-Duff: It could figure out the submarine’s location quite accurately.

At the end of 1942, the Allies installed Huff-Duff finders on numerous warships and thus enjoyed a distinct advantage over the Germans. In order to successfully carry out a “wolf pack” tactic, the submarines had to synchronize their arrival at the combat arena at the exact right moment — that kind of coordination required a great deal of communication. Even if the wireless communications were encrypted, Allied ships could still identify the source of the broadcast. And that was enough to allow them to attack the U-Boats before it was too late.

The Radar

The second innovation was the radar. The germans knew the allies had radar, but the first Radar systems that the British installed on their ships weren’t particularly effective: they could only detect a submarine when it was on the surface and no more than a few miles away, and then only under ideal conditions. The Germans even developed a device that could recognize Radar transmissions, allowing the U-Boats to identify the approaching threat in time to dive to safety.

But in 1942 the British and the Americans began using a new kind of Radar that transmitted radio waves at higher frequencies than were used in earlier designs. This new Radar was not only more efficient and powerful than its predecessors — it was also invisible to the German devices.

The B24 Liberator

The third innovation was a new aircraft: the B24 Liberator.

America’s industrial capabilities were a matter of great concern to the Germans, and rightly so. The production of the Liberator clearly demonstrated the power of America’s enormous and efficient industrial factories: roughly 18,000 aircraft came off the assembly line during the war. That’s more than any other aircraft in history! At the height of production, the US turned out a new plane every 55 minutes. The output of aircraft fuselages at a single Ford Motors plant in Detroit was greater than the output of Japan’s entire aircraft industry — and about half of the production of all of Germany’s aircraft facilities.

The big, blockish Liberator wasn’t much to look at, but it could fly long distances carrying an impressive payload. The British quickly used it to close the Air Gap in the mid-Atlantic — the area in which Allied ships had been most vulnerable, without any support from patrol planes, and where the German U-Boats had hit them the hardest.

Some Germans were concerned that the Allies might succeed in installing Radar systems on their planes, but German scientists dismissed those fears, believing that existing Radar systems were too heavy and cumbersome for an aircraft to carry.

But they were proven wrong. The German experts had based their assumptions on their own development attempts, but they were far behind the British, who, even before the war had placed the highest priority on the development of Radar technology. Beginning in March 1943 the Liberator aircraft were equipped with Radar, and the combination of a long-distance patrol plane, massive armaments, and the ability to locate submarines, both during the day and at night, turned out to be a deadly combination for the German submarine fleet.

‘Black May’

As mentioned before, March 1943 was the most successful month for the submarines — but within just two months, thanks to the Liberator, the Huff Duff, and Radar, the tables had turned. Forty-one German subs — close to a fourth of the entire active flotilla of U-Boats — were destroyed during “Black May.” The Bay of Biscay, whose shores had given the German fleet an enormous advantage over the Allies earlier in the war, had become known as the “Valley of Death”. Many of the U-Boats were destroyed in the bay before even making it to the ocean. Peter Dönitz, the son of the admiral, served on one of those sunken subs.

When spotting an incoming aircraft, the accepted procedure among the submarine commanders was to quickly dive and leave the area. This tactic allowed the sub to escape from the plane but also forced it to lose contact with the convoy it had been lying in wait for. Karl Dönitz believed that the U-Boats could and should engage enemy aircraft in combat. On May 1st Dönitz issued an order: instead of evading an approaching aircraft, U-Boats should fire the cannons on their deck, and try to shoot it down.

It would soon become clear how damaging Dönitz’s order was. Although the German U-Boats were equipped with modern, effective canons and had managed to shoot down more than one Allied plane, Dönitz hadn’t taken into account one simple fact: the British were more than happy to trade an airplane for a U-Boat. The British had a few thousand patrol aircraft; the Germans – had only a few hundred U-Boats. The “Fight Back” order remained in effect for only 97 days before being revoked, but, in that time, the patrol planes managed to sink 20 German subs and seriously damage 17 more, at the cost of “only” 120 planes.

“Black May” had been a sign of things to come. From that point on the German naval forces gradually lost their offensive momentum and the number of ships the U-Boats managed to sink decreased each month. Karl Dönitz realized that things were looking grim, but he did his best to boost morale. He promised the crews that a revolutionary technology would soon transform the combat environment to their advantage… But the Type XXI submarine was still in its initial stages of production and the German engineers hadn’t managed to make improvements to the existing subs and their equipment.

Snorkels and Torpedos

The Germans did introduce two major improvements at the end of 1943. The first was the acoustic torpedo, which homed in on its target by heading for the noise made by the ship’s propellers turning in the water. Previously existing torpedoes were “dumb” in that they traveled only in a straight line or along a predefined route. But the acoustic torpedo could steer itself along the way, thereby increasing its chances of hitting the target.

The second innovation was an idea the Germans “stole” from the Dutch. When Germany occupied Holland in 1940, they captured two Dutch submarines. German engineers discovered that Holland had implemented a new concept: a collapsible pipe that allowed the sub to suck in air for its diesel engine, even while diving at a depth of a few feet. The sound the air pipe made while the engine was running sounded to the Germans like snoring — ‘Schnarchen’ in German. So they called the pipe “schnorchel” (or snorkel).

The Dutch idea had a certain logic: since only the upper end of the pipe stuck out above the surface, the danger of discovery was much lower than when the whole sub surfaced. Even so, the Germans weren’t particularly impressed by the snorkel. As we know, German submarines were designed to spend most of their time on the surface. Diving — in the minds of the German engineers — was mainly for escaping from attack. Therefore, the U-Boats were not intended to spend long days underwater, but only a few hours at a time. The batteries that powered the electric engine were a fitting solution for such short periods of time, and there was no need for the noisy snorkel. By mid-1943, the German subs were forced to spend more and more time underwater while trying to evade Allied patrol aircraft. And that’s when they remembered the snorkel and began installing them on their U-Boats.

The snorkel gave the submarine a small advantage in that the British and American Radar was not able to detect the narrow pipe amidst the waves, so the U-Boat could sneak up close to its target. But it also had disadvantages: for example, a submarine with the pipe up couldn’t go very fast without the thin pipe bending and breaking from the water pressure. Using the noisy snorkel to go faster would also have made the sub’s sensitive sonar almost useless. During the first months that the snorkel was in use, it suffered from very low reliability, especially with the valve that was installed on the upper end of the pipe to prevent water from getting into the engine. Whenever this valve malfunctioned and the supply of outside air was cut off, the diesel engine would suck air from the only available source — which, was the air inside the sub! The air pressure inside the U-Boat would suddenly decrease, leaving the crew writhing on the floor, suffering from intolerable earaches and punctured ear drums.

Floating Coffins

The acoustic torpedo also failed to live up to expectations and only managed to home in on extremely loud targets. It missed ships traveling at a relatively slow speed — such as merchant ships, that were the main targets. In at least two instances submarines sank themselves — the torpedoes they launched locked onto the noise made by the submarine itself and made a U-turn! The Allies also learned to employ an anti-submarine counter-measure — a device for ships to drag in their wake, making a great deal of noise — and rendering the torpedoes even less effective.

The U-Boats’s crews were still eager to fight: they were mostly young men who had come of age in the Nazi school system and believed with all their hearts in the Nazis’ vision of Aryan victory.

But blind faith is no substitute for practical capability. The flotilla of German U-Boats entered 1944 in a sorry state, and the results of the Allies’ technological superiority were unmistakable. During 1944 the U-Boats sank 120 merchant ships, at the incomprehensible cost of 130 submarines. The casualty rate among the submarine crews was 75%: three of every four sailors who went to sea did not return. This was the highest casualty rate in any branch of the German armed forces, on all fronts. Before going to sea on U-Boat, sailors said their goodbyes to family and friends as if they were going toward certain death. The submarines gained a dubious reputation as “floating coffins.”

Otto Merker

The German command was under a great deal of pressure, but the Type XXI model — the new, fast submarine they were all praying would lift them out of the deep hole they were in — still wasn’t ready! The shipyard schedules showed that the first sub of the new model would be completed only in November of 1945 and wouldn’t enter active service until mid-1946. For the Germans – this schedule was unacceptable. The navy command contacted a German industrialist named Otto Merker, who had extensive experience in the mass production of automobiles. They asked him to help accelerate the production of the new submarine.

Merker studied the existing process to identify the major problems. All the shipyards producing the sub worked in serial: each manufactured one part after the other and then assembled them into a single U-Boat. This serial process severely slowed the production: No part was made until the previous part had been completed, and thus it took a year and a half to complete a single submarine. Merker urged the shipyards to change the entire process. Instead of making the parts one after the other in the same factory, each factory should specialize in making a single component of the sub, so that all the factories would work in parallel. Thus Merker managed to shorten the production time per sub to only six months and by the beginning of 1945, the first type 21 U-Boats rolled off the assembly line.

U2511

The first operational type 21 U-Boat was the U2511, under the command of Adalbert Schnee, a highly experienced officer. On April 3rd, 1945, U2511 left the port of Bergen in Norway and headed for the Caribbean Islands to take part in its first patrol mission. It was spotted by British warships, but as its designers had predicted, it used the advantage of its underwater speed to easily escape the ships and their depth charges.

Four days later, on the 4th of May, the submarine spotted a British destroyer, the HMS Norfolk. Adelbert Schnee believed in the combat potential of the vessel under his command and decided to put it to the test. He dove underwater, quickly and quietly slithered between the destroyer’s detection and defensive measures, and positioned his U-Boat at a distance of 1500 feet from his target — a perfect textbook position for attack from which the destroyer had no chance of escaping.

Schnee held fire. In his hands, he was holding a message that had arrived just a few hours earlier: the order for the German armed forces to surrender. Having proven the indisputable technological superiority of his U-Boat, he ordered the crew to turn around and return to Bergen, where he surrendered to Allied forces. A few days later the submarine commander happened to meet Allied officers from the Norfolk and told them about their encounter at sea. At first, the destroyer’s officers refused to believe that a submarine had managed to get that close undetected, but they were convinced once he showed them two entries from the log of the U2511.

The New Fuhrer

Karl Dönitz, like many other military commanders and senior government officials, knew that the war was lost and German surrender was only a matter of time. One can assume that the news of Hitler’s suicide in his bunker in Berlin didn’t come as a big surprise to them. The real surprise was in store for him a few days later, when he learned of the contents of the Fuhrer’s will: Hitler had appointed him, Admiral Karl Dönitz, as his successor. No one, including Dönitz, had expected that dramatic choice. Hitler, on the verge of total defeat and overwhelmed by paranoia, had decided that the Nazi higher-ups such as Hermann Goering and Heinrich Himmler — the more obvious choices — had betrayed him, turned their backs on him in his most desperate moment, and so he decided to anoint the ever loyal Dönitz as the Third Reich’s new President and Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces.

Dönitz received the news of his appointment while at a naval base in northern Germany. The next day, after fleeing from the disintegrating city of Berlin, Heinrich Himmler strode into Dönitz’s office, escorted by six S.S. officers. In his memoir, the admiral described this tense encounter as follows:

“I offered Himmler a chair and sat down at my desk, on which lay, hidden by some papers, a pistol with the safety catch off. I had never done anything of this sort in my life before, but I did not know what the outcome of this meeting might be.

I handed Himmler the telegram containing my appointment. “Please read this,” I said. I watched him closely. As he read, an expression of astonishment, indeed of consternation, spread over his face. All hope seemed to collapse within him. He went very pale. Finally, he stood up and bowed. “Allow me,” he said, “to become the second man in your state.” I replied that was out of the question and that there was no way I could make any use of his services.

Thus advised, he left me at about one o’clock in the morning. The showdown had taken place without force, and I felt relieved.”

An Orderly Surrender

A few days later Himmler was captured by the British and committed suicide by poisoning. Dönitz, on the other hand, harbored no thoughts of suicide. He had a most important mission: to organize the quick and orderly surrender of all the German armed forces, as soon as possible, as every additional death would serve no purpose. His first goal was to transfer as many German soldiers as possible to the western front, thus allowing them to surrender to the British and Americans. The Germans had killed approximately twenty million Russian soldiers and civilians during the failed invasion of the USSR, and their countrymen did not tend to be merciful to POWs — if they even took any prisoners, that is.

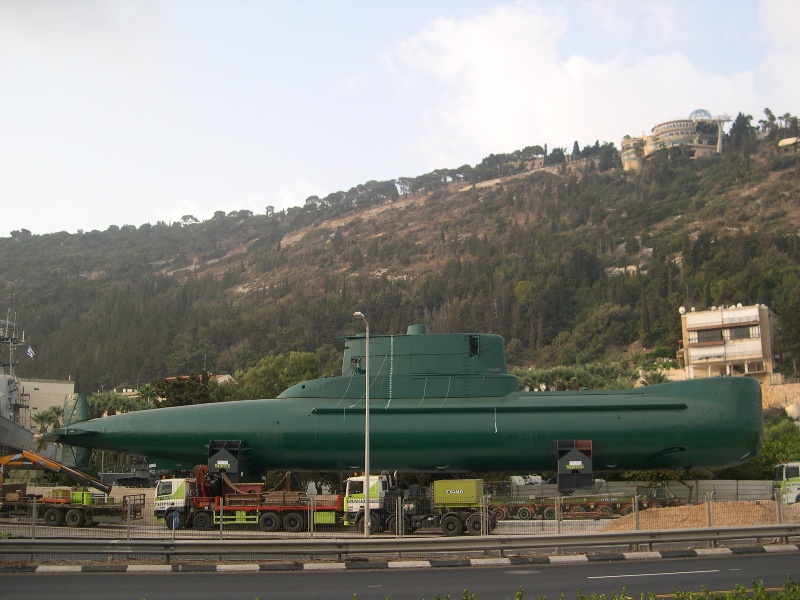

On the 8th of May, 1945 Dönitz ordered the military high command to sign the armistice agreement and the war officially came to an end. The Allies captured about 150 of the once-dreaded German U-Boats. Most of them were sunk in the years following the war, though a few remain on display in museums around the world.

Karl Dönitz was among the accused at the Nuremberg trials and was found guilty of war crimes. However, since he had not been personally involved in the Holocaust or other atrocities, he was sentenced to only ten years imprisonment. He was released in 1956 and spent the rest of his life in a country home in West Germany. He wrote two autobiographies about the war and never expressed any remorse for the important part he had played in the brutal Nazi war machine or for the 30,000 Allied soldiers and civilians that were killed by his submarine attacks. He saw himself as a loyal soldier and German patriot who had followed orders, in the same way that the British, American, and Russian generals had followed theirs. He died in 1980.

A sense of irony – The Israeli’s navy new submarines

So we have seen that the Germans did not lose the war because of cowardice or poor leadership, but mainly because they lost the technological arms race. But despite their defeat in the war, the knowledge and experience their engineers gained while designing and producing the advanced submarine didn’t just evaporate. During the 1950s, as part of the economic recovery of West Germany, the Allied powers allowed them to develop submarines for export — as long as their weight was less than 450 tons, meaning relatively small subs. The Germans salvaged a number of subs from the sea bottom and refurbished them. Later, they also began to export completely new models that were tiny compared to Russian and American nuclear subs, but were quiet and equipped with sophisticated technology. Eventually, that became one of Germany’s most important exports.

Now, here’s an interesting and little-known anecdote. One of the first submarine models that German shipyards developed in the 1960s was the Type 206. The Israeli navy, which at that time was considering a number of Danish and Italian models, decided that the German sub was the best option for them. An agreement between Israel and Germany was signed, but for clearly political reasons it was decided that they would be produced in Britain, rather than Germany. The name of the model was changed to Gal and it successfully served the Israeli navy for many, many years.

The next model the Germans developed, Type 209, is the most commercially successful in the world. Fourteen navies have purchased these subs — including the Israeli navy: these are the “Dolphin” submarines, the most expensive armament purchased by the IDF. In this case as well, the difficult history between the two nations affected the deal, this time in Israel’s favor: the Germans financed most of the cost of the production of the expensive submarines.

So it happened that the State of Israel — home to the Jewish people, whom the Nazis tried to exterminate — was among those who profited most from the success of the German submarine flotilla, which was a great source of pride to Adolph Hitler. Fate, it seems, doesn’t lack a sense of irony…

Ran Levi is a Science & Technology author, and co-host of Curious Minds Podcast. Read More…

Read Other Articles:

- The Indo-European Language: Linguistics & Genetics

- Marine Navigation & The Scilly Islands Disaster

- Stuxnet: The Malware That Struck Iran’s Nuclear Program